Tokyo Mental Health is here to support you and provide you with the help you need.

What is Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)?

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) as the name suggests is defined by two characteristic features; obsessions and compulsions.

Obsessions are intrusive thoughts that come into mind for no apparent reason. These thoughts appear at random, many of which are anxiety provoking and uncomfortable. For example, the thought that one’s hands have been contaminated having touched an elevator panel touched by others. The interpretation by the subject of intrusive thoughts is what characterizes intrusive thoughts as being obsessions and the nature of the interpretation is thought to be important in triggering a consequent fear response.

Compulsions are thoughts and behaviors, often in the form of specific rituals performed to reduce anxiety. These rituals all take time and come with a cost. Sufferers can become preoccupied in performing these rituals with the aim, it is thought, of reducing discomfort. Compulsions can be excessive and, what is worse, are ineffective in reducing obsessions in the longer term, only offering temporary relief. In fact, in certain ways, the compulsions may maintain the anxiety.

How the World Health Organization (WHO) defines OCD

OCD is described as persistent and repetitive obsessions and compulsions or both. Obsessions can be thoughts, images, urges, or impulses that are intrusive and are anxiety provoking. Compulsions are repetitive behaviors and mental acts that one is driven to perform as a response to obsessions. A diagnosis is warranted when obsessions and compulsions consume time (e.g., more than 1 hour a day) or result in significant distress and impairment in social, personal, familial, educational and occupational functioning.

Obsessions

Obsessions vary between individuals and can appear in the form of thoughts and images. They can be characterized as being persistent, repeated and unwanted. There are however several common themes such as:

- Thoughts of contamination

- Difficulty dealing with uncertainty

- Preference for order and symmetry

- Thoughts of losing control and causing harm to self or others

- Aggressive or sexual thoughts

Compulsions

Compulsions can be characterized as repetitive behaviors a sufferer is motivated to complete with the aim of reducing discomfort. Like obsessions, compulsions come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, but typically have common themes such as:

- Checking

- Counting

- Washing / cleaning

- Methodicalness

- Following a fixed pattern / routine

- Asking for reassurance

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder – Diagnostic Criteria

Essential Features (required)

- Presence of persistent obsessions and/or compulsions.

- Obsessions and compulsions are time-consuming (e.g., take more than 1 hour per day) or result in significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. If functioning is maintained, it is only through significant additional effort.

- The symptoms or behaviors are not a manifestation of another medical condition (e.g., basal ganglia ischemic stroke) and are not due to the effects of a substance or medication on the central nervous system (e.g., amphetamine), including withdrawal effects.

Clinical Features (additional)

- The content of obsessions and compulsions are usually in more than one dimension such cleaning, symmetry, forbidden thoughts and hoarding

- Performing compulsions brings temporary relief

- Avoiding people, places and/or things that trigger obsessions and compulsions

- Common beliefs (see Dysfunctional Thinking Habits below)

- Severity depends on amount of time spent in a day on obsessive thought and compulsive behaviors

- Typically, obsessions are followed by compulsions, However in some people, particularly during the initial phases of the disorder, compulsions can precede obsessions. You may first notice repetitive behaviors as being indicative of specific fears before attributing them to obsessive thoughts.

Who gets OCD?

It is predicted that across the lifetime, prevalence of OCD is between 1-3 %. This figure has been shown to be consistent across many countries studied. The onset of OCD usually occurs during adolescents; often in the early 20s in females and late adolescents in males. Early-onset OCD is usually rare with a prevalence rate of about 0.25% for the age range between 5-15 year olds. Early-onset OCD is more likely to be predicted by genetics, more common in males and has been found to have increased symptom severity compared to late-onset OCD. Age can determine the type of obsessions experienced; for example sexual and religious ones for adolescents and fear of death of a parent in children are common.

On a developmental level, factors such as childhood psychosocial stressors (emotional, physical or sexual abuse, death of a parent, serious medical illness or accident related disability), social isolation and stressful life events (e.g., in the postnatal period) have been implicated in playing a role. Psychological factors such as dysfunctional thinking habits, which are often the focus of interventions, are thought to maintain the occurrence of OCD.

Dysfunctional Thinking Habits

- Thought-action fusion: There are two forms of thought-action fusion:

- Having a “bad” thought is regarded by the subject as increasing the likelihood of the thing thought-about actually happening.

- Thinking of bad actions is believed by the subject to be morally equivalent to carrying out these bad actions.

- Inflated responsibility: the inflated belief about the ability to create or avert negative outcomes. The person feels responsible to perform all actions necessary to avert the feared consequence and engages in constant monitoring and behavior checking to ensure their actions or the lack thereof do not lead to the worst case scenario.

- Belief about controllability of thoughts: the belief that it is possible and necessary to control thoughts and images once potential harm has been perceived.

- Perfectionism: The belief that there is a proper way of doing things, and that it is the person’s duty to perform accordingly. For example, ‘Making a mistake’ is regarded as being equivalent to ‘failing completely.’

- Overestimation of threat: the over-estimation of the severity of harm, and that the likelihood of bad things happening is greater unless one acts preventatively.

- Intolerance of uncertainty: the belief that being certain is the key to coping, and that uncertainty leads to inability to cope. This is related to (b) and (e).

What causes OCD?

Most people with OCD exhibit at least one comorbid disorder such as major depression, a phobia, social anxiety, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anorexia nervosa, Tourette’s syndrome, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury and Huntington disease. It has also been discovered that in abrupt early-onset OCD, an autoimmune reaction to Streptococcal infections in the basal ganglia may on some occasions be the cause. Initially termed, ‘pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), it is now known as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). The new definition of PANS is a broader view which includes neuropsychiatric reactions to non-streptococcal infections.

On a neurophysiological level, studies suggest a dysfunction in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuitry. The CTSC model postulates an imbalance in pathways connected to cortical brain regions. Hyperactivity in the Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) as a result of reduced inhibition in the thalamus has been linked to obsessive thoughts. The striatum supports the repetitive and ritualistic compulsions that follow. Neuroimaging studies further show abnormalities in these brain regions such as smaller hippocampus and larger palladium for adult OCD patients. In some studies, pediatric patients with OCD show larger thalamic volume and thinner inferior parietal cortex.

On the genetic level, studies suggest that there is a strong heritable component whereby OCD, like other conditions such as Tourettes syndrome, clusters in families. This is evident in first-degree relatives of people with OCD who are more likely to be at risk of OCD compared to relatives of controls. Several studies consistently obtain a risk percentage of 10% – 12 % for relatives of people with OCD and 1%-3% for relatives of controls. This finding is further supported by studies that find that the further away the degree of genetic relatedness is i.e., first-degree, second-degree and third-degree relatives, the less likely a relative of someone with OCD will also have OCD. Interestingly, in one study, compared to controls, non-biological relatives (spouses or partners of OCD probands with at least one child together) are 2.5 times more likely to have OCD. A proband is a person in the family who was first diagnosed with OCD. In familial OCD, hygiene and hoarding symptoms of OCD were more likely to be present. Familial risk of OCD were also found to be related to the onset of OCD in probands (the first person in the family to obtain a diagnosis of OCD) whereby the risk for relatives was greater in probands with early-onset OCD (≾19 year old) compared to late-onset OCD. In twin studies, twins who share 100% of their genes (monozygotic twins) are roughly twice as likely as compared to twins who share 50% of their genes (dizygotic twins) to have OCD (87% vs 47% risk respectively). Overall, the heritability of OCD from twin studies is estimated at 48%. On a molecular and genetic level, Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have identified several genes that have been implicated in the impairment of cortical-striatal function and possible functional glutamate-GABA imbalance in OCD.

What treatments work for OCD?

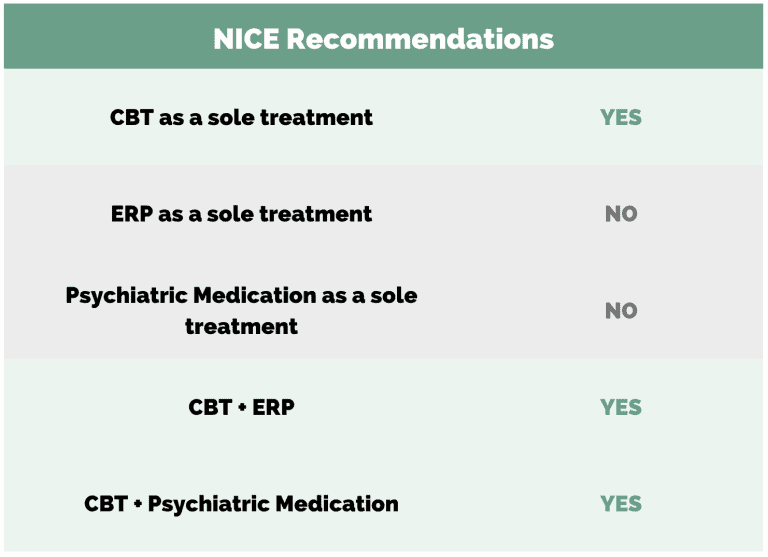

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence United Kingdom (NICE UK) recommends that the principal method of treatment should be Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT). Combining CBT with an Exposure and Response Prevention component (ERP) and/or medication is recommended to achieve the greatest treatment effect.

Medication or ERP as sole treatments is not advised. Antidepressants such as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) can help reduce anxiety and increase response to CBT. NICE reports that in some instances, such as for children and young people with mild functional impairment, guided self help books can be useful. Of note, NICE reports that alternative treatments such as Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Emotions Focused Therapy (EFT), mindfulness and hypnotherapy are commonly requested but these are not recommended for OCD as they are not clinically proven and often do not yield lasting results.

Self-help materials and other resources

If you are keen on learning more about OCD or looking for self-help resources, we recommend:

- Overcoming Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, A self-help guide using cognitive techniques” by David Veale and Rob Wilson

- OCD-UK, A national OCD charity webpage

How can Tokyo Mental Health help?

Make an appointment with us at Tokyo Mental Health for an assessment with our internationally qualified multidisciplinary team of professionals, and we can discuss how CBT and ERP can help you in conjunction with your current treatment plan or be a new starting point in your therapeutic journey As well as psychotherapies like CBT and ERP, we offer counseling, psychological testing and psychiatry services both online and in person. Come visit our Tokyo and Okinawa offices. Our professional psychologists, counselors and psychiatrist will design an individualized treatment plan for you. Contact us for a therapy assessment at our Shintomi office.

References

- Grados, M. A., Riddle, M. A., Samuels, J. F., Liang, K. Y., Hoehn-Saric, R., Bienvenu, O. J., Walkup, J. T., Song, D., & Nestadt, G. (2001). The familial phenotype of obsessive-compulsive disorder in relation to tic disorders: the Hopkins OCD family study. Biological psychiatry, 50(8), 559–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01074-5

- Heyman, I., Fombonne, E., Simmons, H., Ford, T., Meltzer, H., & Goodman, R. (2001). Prevalence of obsessive–compulsive disorder in the British nationwide survey of child mental health. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(4), 324-329.

- Mahjani, B., Bey, K., Boberg, J., & Burton, C. (2021). Genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Medicine, 1-13.

- Mataix-Cols, D., Boman, M., Monzani, B., Rück, C., Serlachius, E., Långström, N., & Lichtenstein, P. (2013). Population-based, multigenerational family clustering study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA psychiatry, 70(7), 709-717.

- NICE Guidelines for the treatment of OCD | OCD-UK. (2005, November 29). OCDUK. https://www.ocduk.org/overcoming-ocd/nice-guidelines-for-the-treatment-of-ocd/

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) – Symptoms and causes. (2020, March 11). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/obsessive-compulsive-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20354432

- Purty, A., Nestadt, G., Samuels, J. F., & Viswanath, B. (2019). Genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Indian journal of psychiatry, 61(Suppl 1), S37–S42. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_518_18

- Rouf, K. (2004-05). Bennett-Levy, J., Butler, G., Fennell, M., Hackmann, A., Mueller, M., & Westbrook, D. (Eds.), Oxford Guide to Behavioural Experiments in Cognitive Therapy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 Apr. 2022, from https://www.oxfordclinicalpsych.com/view/10.1093/med:psych/9780198529163.001.0001/med-9780198529163.

- World Health Organization (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/

- Van Grootheest, D. S., Cath, D. C., Beekman, A. T., & Boomsma, D. I. (2005). Twin studies on obsessive–compulsive disorder: a review. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 8(5), 450-458.