- 2023/08/21

- Self Help & Tips

Author: Udeni Appuhamilage, Ph.D, TMH Psychologist

Embodied cognitions and emotions are familiar to us; we all talk about ‘hunger for success,’ ‘anger that burns the heart,’ ‘a sadness that is hanging over’ or ‘a problem that is eating away at us.’ In a therapeutic setting, these sayings are regarded as metaphorical and as serving to access and symbolize clients’ emotions and cognitions, and sometimes clients’ resistance. However, these same expressions are not only about ‘symbolic expressions’ but also about subjective experiences and existences for the client. How to combine these two perspectives – the mind’s and the body’s? How to analyze the relationship between body and psychotherapy practices?

Mind-body dualism refers to a metaphysical viewpoint that mind and body are two distinct substances, each with its own essential and different nature. Historically, one of the well-known versions of this dualism is credited to Rene Descartes of the 17th century. He distinguished between res extensa – matter extended in space, and res cogitans – the conscious mind; accordingly, the body is an extended material, subjected to material laws while the conscious mind is unextended and immaterial. In contrast, contemporary therapists who challenge the dualistic view, especially those belonging to body-oriented psychotherapy (i.e., BOP), believe that bodily sensations in fact teach us about dysfunctional emotional processes. Thus, beyond spontaneous body language such as posture and gesture, they also use body attuning exercises to invite clients to look into their bodies as a way to develop greater understanding of how clients relate to their experiences.

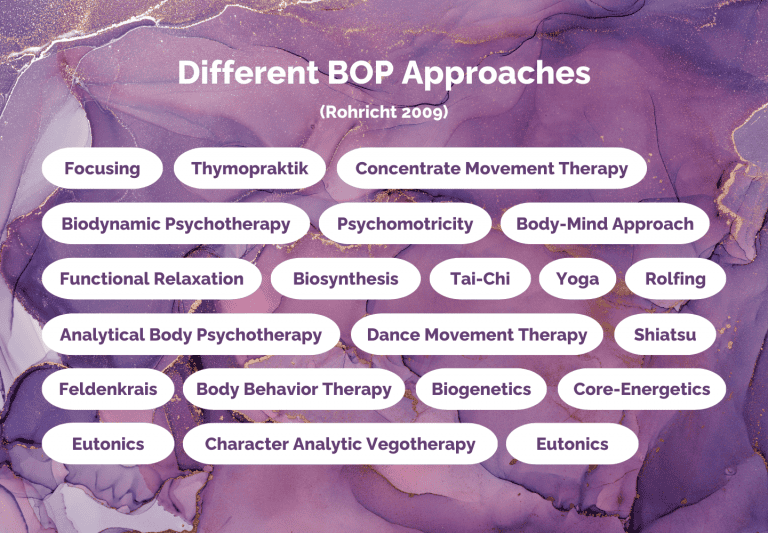

BOP is an umbrella term “that explicitly uses body techniques to strengthen the developing dialogue between patient and psycho-therapist about what is being experienced and perceived” (Heller, 2012, p. 1). It is a diverse field involving many approaches, all of which are connected by their shared recognition of the connection between body and mind, and how our relationship with ourselves and external social-material worlds is rooted in not only our thoughts and emotions, but also our body. According to Rohricht (2009), there is a wide range of BOPs on offer; he names twenty-one categories in his work, as is shown in Figure 1.

In this blog post, I concentrate on only one BOP, namely Gendlin’s (1981) work on focusing and the way this framework validates the body as an important and essential component of not only the therapeutic relationship, but also of the client’s relationship with their own self and life experiences. Focusing is an experiential and embodied process of self-reflection. The name, Focusing, comes from the understanding that this approach requires a specific way of paying attention (i.e., focusing) in order to notice and connect with the ‘felt sense’: what is still vague and unclear about the client’s experience interacting with their situations and environment. The approach holds that focusing on the felt sense allows the client to build an in-depth understanding of their experiences, which would consequently lead to a ‘felt shift.’ In fact, as is discussed in the following case vignette, this process can lead to liberating experiences for the client, and to recognize the capacity of our bodies to move and exist in and with their experiences.

Below is a case study through which I try to explain the significance of focusing in therapy to help clients reach new meanings and growth.¹ Let’s call my fictitious client below Maria. Maria is a 43 years old woman with a diagnosis of depression. Maria shared detailed narratives about her past and the present with her therapist in trying to understand her depression – about the fights she witnessed between her parents, experiences of neglect, forced to keep her knowledge of her father cheating on her mother as a secret, an abusive relationship she had when she was in college, how her husband cheated on her and how she feels nothing towards him despite his repeated apologies. Together with her therapist, she built insight about all these life experiences, identified patterns and interpreted her symptoms. She continued to take medications too. And yet, her depression continued. In one of her sessions, she expressed frustration, questioned why nothing works. She knew she was depressed and that all the insights she built somehow explain her depression. But she also said how she felt as if something was missing. The therapist asked if she can, for a moment, stop looking for rational, logical, clinical explanations and just be with her question: ‘what is wrong with me?’ The therapist invited her to close her eyes and to remain with the question while focusing on the center of her body. Tears started to roll down her cheeks and she started explaining the tears. The therapist gently suggested that she stop interpreting her tears, and instead be with them, to be with the discomfort a little longer. She spontaneously moved her hands towards her face, covering her ears. The therapist verbally acknowledged her bodily movements, encouraging her to fully recognize and connect with the bodily movements.

An image came to her; she saw herself as a child, standing by the door, listening to her parents fighting, hoping that her father would stop hitting her mother. ‘I want you two to stop’ she shouted. The therapist could see that this verbal expression ‘fit’ right as she shouted the same several times. That was not the whole story though, because there still was tension in Maria’s body. They re-visited the bodily felt sense in another session. The therapist encouraged Maria to stay with the body, to see what else was there. She saw another image; this time, it was herself in her room of the student dormitory. Her ex-boyfriend was outside, threatening and demanding that she open the door. Her body moved back and forth on the chair, while her hands continued to cover her face and ears, and tears streamed down her cheeks. Then she said it again, repeatedly: ‘I need you to stop.’ The therapist asked her to keep her attention on her body and see if there was anything else. She saw a third image: herself sitting on the bed in her previous apartment, scrolling through images of her husband partying with another woman. She continued to cry. She felt betrayed, disgusted, angry, let down, worthless, but forced to accept and be with these feelings because she had no income apart from her husband’s salary. She desperately wanted it to stop, but knew that she could not stop it. The therapist asked her if there was anything that she wished she said. She said the same again. ‘I needed him to stop.’ She cried, her hands fell down to her laps and her body was visibly relieved.

Maria never voiced her cry to her parents, her ex-boyfriend or to her husband in real life; instead, she kept it to herself, silenced her own self; ‘I swallowed my pain’ she told her therapist. While Maria had masked this imprisoned pain with verbal interpretations, her body carried the raw feeling in the form of depression. She lacked an expression for it in therapy too, until her therapist tapped into her body not as a symbolic representation of her symptoms but as a container of raw emotions, sensations and meanings. They relied and trusted her body to teach what it was that they could not understand yet and searched ways to give words to what it was that she felt within her body. This process led to a ‘felt shift’ where her body relaxed, since the change was felt in the body. Her past still remained painful; however, after she opened up and validated her bodily knowledge, she could feel relieved even when she talked about these experiences out in the open.

In his classic work on the process of ‘becoming’ a person, Carl Rogers writes: “The client is hit by a feeling – not something named or labeled – but an experience of an unknown something which has to be cautiously explored before it can be named at all” (p. 129). It is this internal point of reference that Gendlin (1984) calls as the ‘felt sense’: “The edge of awareness; a sense of more than one says and knows, an unclear, fuzzy, murky sense of a whole situation, that comes in the middle of the body: Throat, chest, stomach, abdomen” (p. 79). The body, in focusing, is not the physiological and redundant machine that we refer to in the conventional use of the word body. Instead, focusing refers to the body as ‘sensed’ from within. The focusing therapist encourages and facilitates the client to restore contact with that sense of the body, to reconnect with stored and/or imprisoned experiences so that the body can restart moving and evolving, thereby revealing new meanings for those experiences. Focusing requires the therapist to stay with the felt sense with curiosity and non-judgment, to build an attitude of patience, to be ready to accept vagueness and pause ongoing processes so as to create space for new meanings.

For the most part, our daily lives are regulated by external tasks, and we hardly pay attention to our inner, bodily-felt experiences. Focusing teaches us to wait, and ‘be’ with the body and all its sensed experiences. We all know that our bodies know more about our environment including the people around us than we can consciously recognize. Connecting with these bodily felt senses can surely enable us to understand and create new meanings of our lives, relationships and challenges. When these new meanings unstick us from our previously imprisoned experiences, we feel relieved and energized, ready to move forward with a newly formed relationship with ourselves.

¹ The case does not reflect an existing or a past client.

References

- Gendlin, E. T. 1981. Focusing (Rev. ed.). New York: Bantam Books.

- Gendlin, E. T. 1984. The client’s client: The edge of awareness. In F. R. Levant & J. M. Shlien (Eds.), Client-centered therapy and the person-centered approach: New directions in theory, research and practice (pp. 76-107). New York: Praeger.

- Heller, C. 2012. Body psychotherapy. History, concepts, methods. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Rogers, C. R. 1961. On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Rohricht, F. 2009. Body oriented psychotherapy. The state of the art in empirical research and evidence based practice: A clinical perspective. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy 4(2): 135-156